“There he sat with his hand on the tiller in the sun, staring at the Lighthouse, powerless to move, powerless to flick off these grains of misery which settled on his mind one after another. A rope seemed to bind him there, and his father had knotted it and he could only escape by taking a knife and plunging it... But at that moment the sail swung slowly round, filled slowly out, the boat seemed to shake herself, and then to move off half conscious in her sleep, and then she woke and shot through the waves. The relief was extraordinary. They all seemed to fall away from each other again and to be at their ease, and the fishing-lines slanted taut across the side of the boat.“ -Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

https://beckettodd.substack.com/p/19835007-1c2a-46b8-8a20-f041a7eb09ec

A news headline today reads: “Texas Barge Crash May Have Spilled 2,000 Gallons Of Oil” into Galveston Bay after the barge hit a bridge. Back in March (2024) a 2.5 mile long oil spill was reported off of Huntington Beach, California. Also in March the Heiltsuk Nation in British Columbia asked the UN to address damage from 110,000 litres of oil released by a tugboat into Gale Creek on BC’s central coast. Etc. You get the picture.

My dad, the ecological designer John Todd, has been working on using designs that use nature’s processes to clean up water in situations like this for many decades. He’s now 85. In a recent proposal, he wrote: “Recently we have begun to rethink our approach to improving coastal water quality. For the past few years Ocean Arks International [his not-for-profit institute] has been designing and engineering marine technologies capable of supporting environmental restoration in the bays and estuaries of Cape Cod, our home base. However our technological approach to water quality improvement lacked optimal systems complexity and integration. On analysis, our proposed use of gravel barges to house the eco-machines seemed less than optimal, particularly within the important intertidal zones.

“Fortunately two insights changed everything for us. First, the concept of a fleet of sailing vessels that look like yachts, but which will house on-board eco-machines, was born. They would be powered by the wind and the sun and not need fossil fuels to carry out their water purification mission.”

Picture this. A fleet of pretty old-timey sailing vessels arrives and moors at a local yacht club near the site of a recent oil spill. Their flat-bottom design is based on Thames sailing barges from the 19th century, which carried cargoes between London and the coastal towns of eastern England. By the turn of the 20th century these barges also carried cargoes across the North Sea to the coastal lowlands of Holland, Germany and Denmark. They can cross rough seas and, because they have “leeboards,” or raisable rudders on each side of the boat, they can sail into very shallow water.

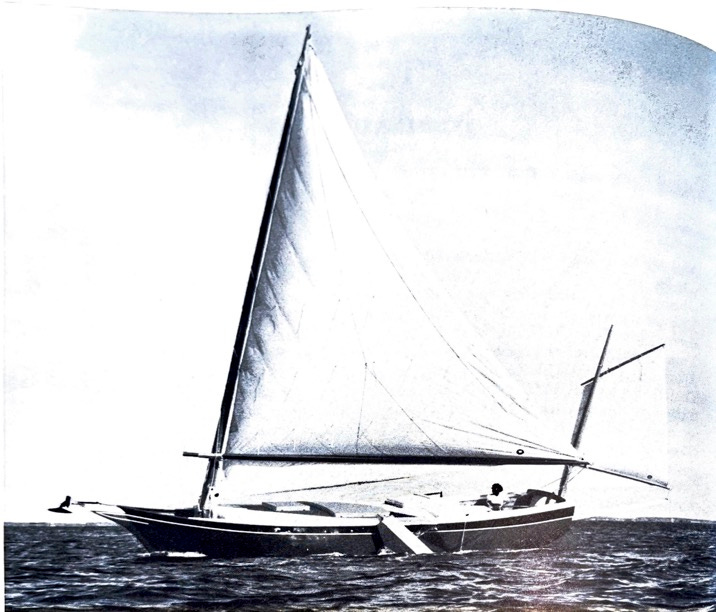

More proximally, the boats in this fleet are scaled up versions of a design for a modern day sailing barge called the Manatee, which my dad only recently learned that my grandfather, Robert Todd, commissioned from the late naval architect Phil Bolger. The Manatee is a pretty boat, with a large triangular sail in the front and a smaller four-cornered sail in the back.

But here’s the thing. Each of these pretty boats contains an ocean restorer system, which draws on nature’s designs to clean up the polluted water. Tanks inside the hulls of the boats house a diversity of beneficial organisms, including microorganisms, plants, fungi and animals that clean contaminated water through a series of steps. Dirty water goes into the restorers, clean water comes out.

The sails double as solar “panels” and generate electricity. The power is used for propulsion, aeration, pumping and water circulation into, and within, the vessel’s eco-machine, which is a designed ecosystem that cleans the water that is pumped through by a windmill attached to a mast. The forward movement of the boats moves polluted water through the living technology system.

The fleets are romantic, inspired by naval and family history, and they’re beautiful too. They use living technologies finessed by my dad’s doctoral training as a biologist and many years of observation, experimentation and ecological design. And they serve a desperately needed purpose. They draw on multiple strands of deep knowledge as well as exceptional creativity.

But this is not a post about sailing ships, ecological design, or ecological devastation of our waters. I’m a cognitive scientist and this is a post about that the potential for creativity made possible by the aging mind and brain. Using my dad as the poster child, I’m going to argue that age can bestow levels of creativity that are unavailable to us when we’re younger. I’m not the first or the only person to make this argument, but it’s been a long time coming. And I’m also going to talk about evidence that complex brain dynamics shift with aging, and that failure of the brain dynamics to make these shifts is associated with lower quality of life.

Dr. Lynn Hasher is Professor Emerita in the University of Toronto Psychology Department and Senior Scientist at the Rotman Research Institute in Toronto. She has devoted many years to studying how cognition changes as we age. At first her line of research, like all other aging research, framed age related changes strictly in terms of decline – with 18-22 year old Psychology majors serving as the comparison group and the model for normal optimal cognitive function for all people for all time. (Tangentially, I recently read a very effective critique of this ubiquitous comparison to “normal” populations in the book Empire of Normality: Neurodiversity and Capitalism by Robert Chapman. I highly recommend it.) One of Hasher’s earlier contributions, which captured attention and spawned many further research projects by her lab and collaborators, was the observation that older adults are more distractible than young ones. That is, when sitting in front of a computer doing boring experiments where they have to attend and remember arbitrary and meaningless words, images or shapes, undergraduate Psychology majors are focused machines. They attend to what is relevant to the goals of the task and screen out what doesn’t matter with admirable efficiency. Older adults (in their 60s and up) not so much. They just let more information in – whether it’s relevant to the arbitrary experimental task or not. They also do worse on tasks that measure working memory, or the ability to hold in mind and manipulate a specific set of items (numbers, letters, words, shapes) because they have “leaky” attentional habits and let other stuff in.

The language of the reporting of these findings was – and is still to a certain extent — all about “deficits”. Older adults are said to have “deficits” in attention and the capacity to inhibit information and a “decline” in ability to call up specific memories. Intervention studies have therefore focused on restoring the deficits by finding ways to train an 80 year old brain to be more like a 20 year old brain. But why would you want to do that? Why would an 80 year old want a 20 year old brain? How much experience, knowledge, information, wisdom — how much life — would you need to wipe out to get that youthful brain back? Maybe 80 year old brains are different from 20 year old brains for a reason.

The language of most cognitive psychology and neuroscience claims about cognition and aging is still primarily framed as negative. But as the research findings build up, it’s become clear that there are gains as well as losses. It turns out that older adults perform very well at implicit learning and memory processes, where we pick up and use information without necessarily being aware of it. Older adults pay attention to information not directly relevant to the task at hand - and they remember that information implicitly and can put it to use in the future if it becomes relevant. What’s more, this is not at the expense of their retention of “task-relevant” information (both perceptual and conceptual). This is demonstrated in laboratory tasks involving statistical learning, which is learning to recognize and predict patterns in the environment, and priming, which involves picking up unconsciously on information that is irrelevant at the time, but then being able to use it later when it’s needed.

For a more everyday example of this, suppose you are walking from the house to the garage to get a hammer, and you register that there is a blue watering can sitting on the porch on the way. The watering can is irrelevant to your goal of finding the hammer and putting up a picture. But on some level you notice it without explicitly making note of it. You are perfectly capable of also noticing where the hammer is, getting it, and putting up the picture. And when your daughter asks you where her watering can is you know you’ve seen it, and by retracing your steps can point her to it. When she went out to her car to go to work, past the watering can, she didn’t see it because she was so efficiently focused on information relevant to her task. Maybe a lifetime of experiencing unexpected events teaches you that the information you think is immediately relevant can turn out be less relevant than something else, and your habits of attention expand to retain more possibility. Hasher’s former student Karen Campbell, now a professor at Brock University writes, “contrary to popular belief, they may actually know more than younger adults about the world around them, including how seemingly irrelevant events co-occur” (Campbell et al., 2012).

Campbell also did a study that found that older adults’ capacity for memory – in particular being able to recall that one object was encountered alongside another object — is not in fact worse than that of young adults. It’s just more selective. Older adults remember when it’s relevant. They don’t bother to devote the resources when it isn’t. Here the researchers found older adults showed worse associative memory (memory that two or more things typically appear together) for unrealistic grocery prices than young adults but just as good memory for realistic ones. That is, they filtered for what’s relevant.

Older adults also hang on to recently encountered information for longer and link or associate that information with other information. Campbell et al., 2013, conclude “In fact, what constitutes the present moment or “the now” may, as a result, be broader for older adults.” (The sense of time changes! -- We’ll get back to this in future posts). Older adults tend to have poorer memory for detail but better memory for gist: “While loss of detail is generally thought to be indicative of memory failure, older adults may be better poised to see the ‘big picture,’ as their linking together of ideas may be less constrained by temporal proximity.” Again - when you have more information to contend with in memory, you need to extract the information that’s important to work with. And also, creativity.

So lately researchers have been looking for direct links between aging and creativity. A study by a group at the University of Michigan found that older adults did better than younger adults at a measure of creativity that involves finding creative uses for a brick after reading a scenario that contained distracting words they had been instructed to ignore. This study provided a direct link between porousness to distracting information and creative performance.

But links between aging and creativity were being made as far back as 2011, when Hasher co-authored a paper titled Cognitive Aging: A Positive Perspective. Here the authors outline ways in which lab tests are biased to underestimate the abilities of older adults. For example, lab settings are stressful for older adults and the tasks tend to be arbitrary and lacking meaning (as I’ve mentioned, undergraduate Psych majors are used to that). By way of contrast, the chapter describes amazing aircraft rescues by pilots, all of whom were near the age of forced retirement, arguing that a lifetime of training and experience was required to pull these rescues off. The authors then go on to summarize the landscape of what was known about changes in cognitive abilities with age. In a nutshell, the capacity for effortful retrieval of conscious episodic memory, or memory for specific events, declines with age. However, semantic memory, or memory for factual information un-moored from the context/events in which it was acquired, is preserved. We also rely more on implicit processing and expectations based on prior knowledge as we age. This typically works for us, although we can be slower at updating our expectations and can miss information that isn’t consistent with them, and therefore fail to update them. In general, decision making is more intuitive, and most of the time benefits from greater experience. Older adults also tend to do better at decision making when they rely on their gut emotional responses, which have been tuned through a lifetime of experience. In a more recent paper by Hasher and her former student Tarek Amer, now a professor at University of Victoria, the authors add: “Older adults outperform younger adults on tasks in which optimal performance depends on: (i) accounting for previous decisions within the context of the experiment; and (ii) incorporating accumulated knowledge to reason about social conflicts or make sound financial decisions.”

So older adults often do worse when tested in lab settings, but better in real-world situations where they are able to draw on both the relevance of the information and their experience to perform. They are better at seeing the forest for the trees. Importantly, what has been described as a failure of inhibition in older adults can be reframed as openness to a wider range of information and the ability to intuitively draw and act on multiple threads of extensive knowledge and experience. These qualities are hallmarks of creativity.

So let’s see some of this creative performance in action. I asked my dad to describe what he remembers of the moment he had the series of insights that led to the design of a fleet of sailing ocean restorers.

“I was in the house. It could have been early in the morning. First I saw an image almost like a dream and, what I saw going across the water was little ships and lots of them instead of the behemoth that I had been thinking about calling the ecological hope ship. And then what began grafting itself onto the image was the idea of a fleet, lots of little ships. That was what came to mind.”

A second insight came right on its heels. “Most sailboats are seen as toys and so, in the larger cultural context, irrelevant. I was seeing that their main attribute is that the wind moves them. In the world of yachts, that’s not an attribute that people admire. And in water purification, water is always brought to the treatment plant. But here the treatment is like a floating plow if you will. Sailboats without the need of fossil fuels are moving through the water and are able to treat vast volumes without the pitfalls of energy consumption. The energy was always in the wind.”

One third and last element followed. “I want the sailing ships of the future to be wooden. Nobody is thinking like that. I’m thinking all the time of how to connect the land, the sea, in new ways that can produce different kinds of complex ecological economies. Here that the need right from the start is to connect the ocean fleet to the regrowing of forests.”

“Then after the original moment when it came to me, I was cruising around the concept looking for the fatal flaw and thinking this is going to get a lot of ridicule maybe.” He also drew a picture of the fleet he had seen in his mind’s eye.

There were many long-term streams of thinking that suddenly came together in this classic “aha” moment. First, he had recently seen a travel show that had featured toy boats on a pond in Luxembourg gardens in Paris, and he thinks that was what triggered the image in his mind.

“At that time I was starting to think again about the Thames river sailing barges which I’ve been thinking about for several years. The reason why they’re appealing is that they are flat bottomed and can sail in two feet of water or less, leeboards up. Because of the leeboards, if you look through the cross section, the centre is like a rectangular box that would make a strong container for an eco-machine. It’s the only boat capable of sailing in very shallow water, seaworthy in the North Sea and the Baltic, and the centre of the boat is a rectangular box that can hold an eco-machine. It is ideal for safe onboard eco-machines.

Up to that point he hadn’t thought of eco-machines on barges. But years ago he had been asked to create a sewage treatment system on a theatre barge run by the Caravan Stage Company. He says it was not successful because there were accommodations and other things going on in the centre of the barge where it was. In contrast, ”In the current design the whole middle section will be dedicated to the eco-machine, not used for accommodation or anything. Aft there is space for a kitchen and forward there is enough space for sleeping and washing and a small toilet. The two ends is where the people part of the equation is.”

“The other thing I haven’t mentioned is that the sailing boat I envisioned was a larger version of the Manatee, the ship that Dad had commissioned. I had been thinking of it for the past months as a model. But I hadn’t gotten to the fleet to know what I was doing. I had been staring at it, opening the book, closing the book, looking at Wooden Boat magazine and saw another boat that looked a bit like the Manatee. I thought this boat would be my way of saying to my father ‘I’m sorry I screwed up and didn’t know or appreciate what you were doing.’”

“So there had been these areas I had been poking around in, not making connections between them.” When he had the moment of insight, he said, “I was really excited. I thought here’s another project I don’t know how to fund. But it’s at least less expensive than the ecological hope ship. It becomes obsessive. Every time I blinked I could see this fleet on Waquoit Bay, making it better.”

Does he think his creativity has increased with age? “I’m always a bricoleur and trying to put things together in new combinations,” he responds. “But there’s no doubt in my mind that the most creative period in my life began in 2019 and continued for several years.”

Needless to say, as the mind evolves, so does the brain. Some of most meaningful (IMO) work in that area that has been done by Dr. Randy McIntosh, former head of Toronto’s Rotman Research Institute and current head of the Institute for Neuroscience and Neurotechnology and Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. McIntosh’s work has focused on the brain as a complex dynamical system that must constantly balance processes of information integration – pulling information together – and segregation — keeping information distinct. The overall idea is that the richer and more complex the brain dynamics, the richer the repertoire of cognitive functions they support. Up to a point. Because it’s all about balance. Working with Dr. Cheryl Grady and other collaborators at University of Toronto, McIntosh has studied the way these complex dynamics shift with age. Their research has found that, in healthy aging, the brain relies more on information that is instantiated in more smaller-scale local brain dynamics relative to larger-scale global dynamics. “This balance is associated with better cognitive performance, and interestingly in a more active lifestyle. It also seems that the lack of this shift in local/global balance is predictive of worse cognitive performance and potentially predictive of additional decline indicative of dementia.” (McIntosh, 2018). Interestingly, the more the brain dynamics resemble those of younger adults the worse the overall outcomes as measured by these studies. So what do we take from this? As a complex system, the aging brain does business differently. Older adults have a whole lot more to remember. So it stands to reason that they are working with a whole different kind of landscape of neural possibilities. Older adults have a lot more years of lived experience - which most laboratory tasks simply don’t capitalize on - and they have less space and raw focus power than young adults. As the aging brain has more information to work with, the optimal balance of integration and segregation should naturally shift.

Interestingly, my dad attributes his enhanced creativity to greater confidence rather than greater experience/knowledge or a shift in cognitive style. He thinks he had this depth of synthetic thinking when he was in his 30s – he just lacked confidence.

“Gestation periods that go on all the time may not be age dependent. The only difference age may have is that you have an idea that’s unusual or unorthodox you can face it without panic or fear of ridicule.”

“Suddenly she remembered. When she had sat there last ten years ago there had been a little sprig or leaf pattern on the table-cloth, which she had looked at in a moment of revelation. There had been a problem about a foreground of a picture. Move the tree to the middle, she had said. She had never finished that picture. She would paint that picture now. It had been knocking about in her mind all these years.”

-Virginia Woolf, To the LighthouseReferences

Amer, T., Wynn, J. S., & Hasher, L. (2022). Cluttered memory representations shape cognition in old age. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26(3), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.12.002

Campbell, K. L., Hasher, L., & Thomas, R. C. (2010). Hyper-Binding: A Unique Age Effect. Psychological Science, 21(3), 399–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797609359910

Campbell, K. L., Trelle, A., & Hasher, L. (2014). Hyper-binding across time: Age differences in the effect of temporal proximity on paired-associate learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40(1), 293–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034109

Campbell, K. L., Zimerman, S., Healey, M. K., Lee, M. M. S., & Hasher, L. (2012). Age differences in visual statistical learning. Psychology and Aging, 27(3), 650–656. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026780

Carpenter, S. M., Chae, R. L., & Yoon, C. (2020). Creativity and aging: Positive consequences of distraction. Psychology and Aging, 35(5), 654–662. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000470

McIntosh, A. R. (2018). Neurocognitive Aging and Brain Signal Complexity. https://doi.org/10.1101/259713

Yang, L., Kandasamy, K., & Hasher, L. (2022). Inhibition and Creativity in Aging: Does Distractibility Enhance Creativity? Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 4(1), 353–375. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121020-030705

Zimerman, S., Hasher, L., & Goldstein, D. (2011). Cognitive ageing: A positive perspective. In N. Kapur (Ed.), The Paradoxical Brain (1st ed., pp. 130–150). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511978098.009

Many of the studies on aging using traditional psychometrics, e.g. IQ tests, confound time failures with content failures. Unforunately, normative data does not allow for untangling this confound. But, given that the aging process slows speed of response, failure to discriminate these results in assignment of cognitive decline to what is probably more realistically, a slowed, but possibly more reflective, speed of processing.

Rebecca! What a wonderful surprise to receive your email and read about your exciting research! You are your father’s daughter and great minds think alike! It is hard to believe he is 85 but not at all hard to believe that he is still working tirelessly to design and create sustainable ways to save the environment. Your work is equally amazing and impressive! I am turning SEVENTY (OMG!) in October. I am thrilled to know that I am not necessarily destined to become a senile old lady. I’d like to think I have many years of relevant life experience and that my creative mind is still very much alive. Your research is beyond intriguing. Thank you for including me in your post! So great to hear from you! Love, Merle