We have more than enough kitchen tables

We have more than enough reasons to love ourselves as we are

We have more than enough clarity...

We have more than enough community

We have more than enough pathway

We have more than enough guidance

- from "Abundance Poem" by the participants in “Already Been Done”I’m currently on sabbatical and I’ve spent my time so far this fall based in Montreal connecting and building collaborations with people in a variety of fields who are approaching healing and health from an eco-social perspective. That is, they are taking a systems oriented approach that spans nested levels of analysis, from molecules and cells to large-scale brain systems to whole people in relationships in communities in cultures, in order to understand processes that foster ill or good health. They have taken a lot of time learning to talk to each other across disciplinary silos, building the kind of healthy academic soil ecology I aspire to in my own community. But I’ve also used the sabbatical as an excuse to interview people who are engaged in actions that nurture healing in dark times, and who in fact restore my faltering faith in humanity.

Up to now in this series I’ve been focusing mostly on topics related to brain aging, neurodivergence, neurodegeneration. As a cognitive neuroscientist, that’s the level I tend to engage with. But that’s not the only level of analysis I’m interested in exploring. Whether brains or duets or neighborhoods or gardens, it’s all about (nested) ecosystems. So this post is the first of at least two focusing on the broader level of human communities. And part of the theme that’s emerged is that of communities that have self-organized to arise, phoenix-like, from conditions of devastation.

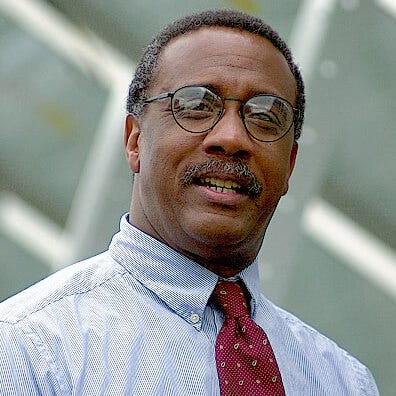

In the first of these pieces I will introduce someone I’ve known for a very long time. Greg Watson is currently Curator of the World Game Workshop and World Grid Project at the Schumacher Center for a New Economics. I’ve known him since I was a teenager, when he took over the reins of the New Alchemy Institute, which my parents had founded. I know him first as a lover of Yogi Berra, Buckminster Fuller, and Bob Dylan and a hilariously on-point political cartoonist as well as the best of friends to my parents. But he’s also a hugely creative systems thinker and community organizer who has never feared taking on political roles to gain leverage to change the state of a system.

There is a great interview with Watson in The Weekly Anthropocene

Also, below is a fairly comprehensive biography from the Schumacher Center website – which will be important for understanding the projects he refers to in our interview below.

Watson has spent nearly 40 years learning to understand systems thinking as inspired by Buckminster Fuller and to apply that understanding to achieve a just and sustainable world. He was part of the community organization Boston Urban Gardeners (BUG) in the 1970s. In 1978, Watson organized a network of urban farmers’ markets in the Greater Boston Metropolitan Area. He served as the 19th Commissioner of Agriculture in Massachusetts under Governors Dukakis and Weld from 1990 to 1993 and under Governor Deval Patrick from 2012 to 2014. During the Patrick administration he launched a statewide urban agriculture grants program and chaired the Commonwealth’s Public Market Commission, which oversaw the planning and construction of the Boston Public Market. From 1984 to 1990 Watson served as Assistant Secretary in the Massachusetts Executive Office of Economic Affairs, where he established and chaired the Massachusetts Office of Science and Technology. In 1988 he presented a paper entitled “Preparing Policymakers To Address the Problem of Climate Change” at the Second North American Conference on Preparing for Climate Change in Washington, D.C. Watson gained hands-on experience in organic farming, aquaculture, wind-energy technology, and passive solar design at the New Alchemy Institute on Cape Cod, first as Education Director and later as Executive Director. He served as the first Executive Director of the Massachusetts Renewable Energy Trust and was Executive Director of the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative, a multicultural grassroots organizing and planning organization for which he initiated one of the nation’s first urban agriculture programs. In 2005 he coordinated the drafting of “A Framework for Offshore Wind Energy Development in the United States” and the following year founded the U.S. Offshore Wind Collaborative. He served on President-elect Barack Obama’s U.S. Department of Energy transition team in 2008. In 2015 he founded the Cuba-U.S. Agroecology Network (CUSAN) following a trip to Cuba to learn about its agroecology system. CUSAN linked small farmers and sustainable farm organizations in both countries to share information and provide mutual support.

The idea of communities self-organizing from the ashes came to me when I was reading descriptions of Watson’s work as a community organizer with the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative in Boston in the mid 1990s, and of what he observed in Cuba ten years ago. That is, I observed that he described the kind of sustainable, participatory, cooperative community initiatives that we so often dream of but inevitably fail to realize. Yet the examples he described arose in places that had been literally razed and abandoned. A bit later I heard a similar story from Eli Oda Sheiner, a doctoral student in anthropology who has spent time in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside — the original Skid Row. My interview with Sheiner will be the focus of a future post. But as an illustration of the tension that implies, Sheiner likes to show an image of graffiti from the Downtown Eastside: DTEStopia. Dystopia? Utopia? You decide.

When I mentioned my observation to Watson, he pointed me to a book by Rebecca Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell. In the book Solnit describes often underreported tales of how, in the wake of historical disasters (the great San Francisco Earthquake, 9-11, Hurricane Katrina) people found community, purpose, and even joy. Temporarily. What I’m proposing is consistent with her idea that disaster can bring out the best of us, that we often find collaboration when forced to for survival. But I want to take it a step further to suggest that Watson’s and Sheiner’s stories illustrate the idea that brief momentary windows of ecologically sustainable community sensemaking, those community utopias some of us have dreamed of, arise when there are no other options.

In the end, Watson is such a good storyteller I could find very little I wanted to edit or summarize from the interview. So I have pretty much just reproduced the lightly edited interview below.

Participatory Sensemaking

This series focuses on the idea of Participatory Sensemaking in many forms. Following the practice of Adrienne Maree Brown and the Emergent Strategies Podcast, which has had a huge influence on my thinking, I begin our interview by asking Watson if the idea resonates with him.

I say, “I'm doing a series on participatory sensemaking. What exactly is participatory sensemaking? I would describe it as a focus on the dynamics of relational interactions, and individual agents in relation to an emergent interaction process that takes on a life of its own, in continuously determining what matters. Does this idea resonate with you? Can you link it particularly to food justice initiatives? If so/not why?”

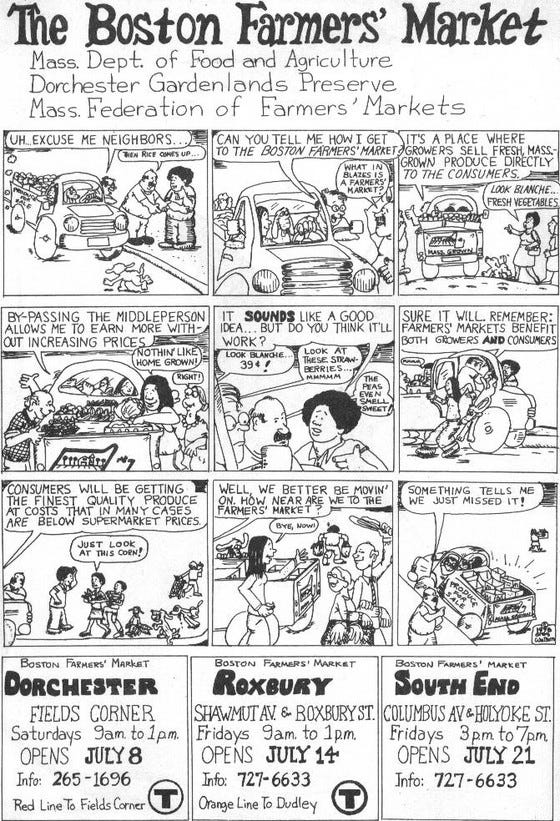

Watson responds, “I think for me, the part of that concept that resonates is the networking that we did — in the Boston Urban Garden project (in the 1970s), organizing was what we did. The idea of organizing obviously is bringing people together and creating the collective synergy of group actions. And to a certain extent, you know, the Boston Urban Gardeners were a sort of pre-internet, real networking organization where we got to know each other and we realized that the face-to-face meetings, bringing the people together, in many cases over food, was a way for us to identify what the community strengths were, what people did.

“And even if people weren't initially interested in urban gardening, many of them had resources or expertise that could help in the efforts to organize community gardens for people who didn't have backyards, and certainly did not have access to any of the resources to grow food, including land, but also tools. So we talked about networking and networking led me to realize that there is a concept of self-organizing entities, and we create entities that are literally greater than the sum of their parts. That to me was really important. And trying to figure out what I wanted to do from that point on it really was — whether it was in food, energy, or shelter — it really was to be an organizer, to create those types of entities that fed off each other and that did create these wholes that were greater than the sums of their parts.

“The Boston Urban Gardeners were early in my tenure here in Boston. You know, at that point, I didn't know what a community organizer was. I was just invited to participate in this group that was trying to find ways of empowering neighborhoods through developing ways of producing their own food. So this was early in the 1970s. Now remember, too, this was during the Vietnam war, the civil rights movement, the women's rights movement, it was a tumultuous time. There was also a community organizing culture — the Industrial Areas Foundation, Saul Alinsky, there were people who felt that they had sort of a handle on a methodology, a way of doing community organizing. But their way of thinking about community organizing focused on black hats and white hats. You identified the enemy and then you went after that. And what I liked about the Boston Urban Gardeners was the fact that they did away with that. They just said, ‘No, we're basically just focused on what we're trying to do.’

“And we would work with the city of Boston. We would work with the city government. We would work with folks that we were told you don't try to work with. We were told, ‘You're going to be co-opted.’ So that was the context and I didn't have any real, formal notion of what I was getting into.

“And this is important: It felt good. I really liked being a part of it because we got together, as I said, and we discussed things. It was a very diverse group. But we fed off each other, literally, figuratively. It felt right.”

Trimtabs and Boston Urban Gardeners

Watson has multiple examples of communities who have been able to use systems thinking to skillfully identify and leverage a relatively small amount of energy to change the state of an entire system in ways that are not always predictable — but can often be beneficial. He likes to invoke Bucky Fuller’s idea of a trimtab.

Watson explains, “A trimtab is a concept that I got from Buckminster Fuller's concept of whole systems. Bucky felt that in any whole system, because every part is interconnected, there are points of leverage that allow you to take a small amount of energy and resources and effect big change. Even to the point where you can change the course of a whole system if you know where those points of leverage are. You start with the whole. You understand what that whole system is to the extent that you can. And when you do that, you can identify where the various points of leverage are. And those trimtabs can be technological innovations. They can be policies. They don't have to be physical artifacts. It’s a point or points of intervention. The example that Bucky used was the concept of a large ocean liner that's huge in mass and momentum because it's cutting through the ocean. The ocean itself provides resistance in terms of being able to change the ship’s course unless you apply a great deal of energy to turn the rudder. Unless you apply the trimtab, the small rudder just above the surface of the water. By turning that with a little bit of energy, you create a partial vacuum, which then sucks the rudder over and turns the ship. So that's the metaphor and that's the way I usually like to think about it. But it's a way of saying, ‘Where are the points of leverage?’

“Can I give you an example? In 1976 the Massachusetts Department of Agriculture realized that the state’s agriculture was on the skids. Beginning at the end of the Second World War all the way up until the 1970s, we were losing farms at an alarming rate and, along with it, obviously farmland. Many people felt that ‘Well, you know what, that's okay. Massachusetts, we're a high tech state. And so what if we have to depend upon outside sources for food?’ We were importing a lot at the time anyway.

“So the idea was that we would relinquish our ability to grow food — ’big deal, we'll import it.’

“But fortunately, Massachusetts Agriculture Commissioner Fred Winthrop said, ‘No, we can't let that happen.’ So he put together a blue ribbon commission that was headed by Harvard economist Ray Goldberg. They put together this incredible report that probably today a consultant would charge $500,000 for. But this was all volunteer. And they analyzed the food system as a whole. In the preface, they even talk about whole systems. I was amazed when I read the report.

“And then they issued a policy for food and agriculture in Massachusetts. I think we were one of the first states to do that. And they talked about the things that we could do to address the hemorrhaging of our agricultural economy.

“And oh, by the way, it was done with the caveat that these would be things that we could do by ourselves. Let's pretend there's no federal government, what could we do as a state within our own means? And so the first big one was that we needed to do everything we can to preserve the existing prime agricultural land. That involved a lot of money. It meant creating something called the Massachusetts Agricultural Preservation Restriction Program. So we purchased the development rights of farms. Farms are being pressured by development. We say, ‘Look, we'll pay the farmer the difference between the development value and the agricultural value. (We say to the farmer): ‘You get the cash. You can do whatever you want to with that. And you still own the farm, but we've purchased the development rights. You can't develop it. So it's going to remain in agriculture forever. You can sell it. But that's a restriction that we've put on it with the money we give you.’ It took a lot of money.

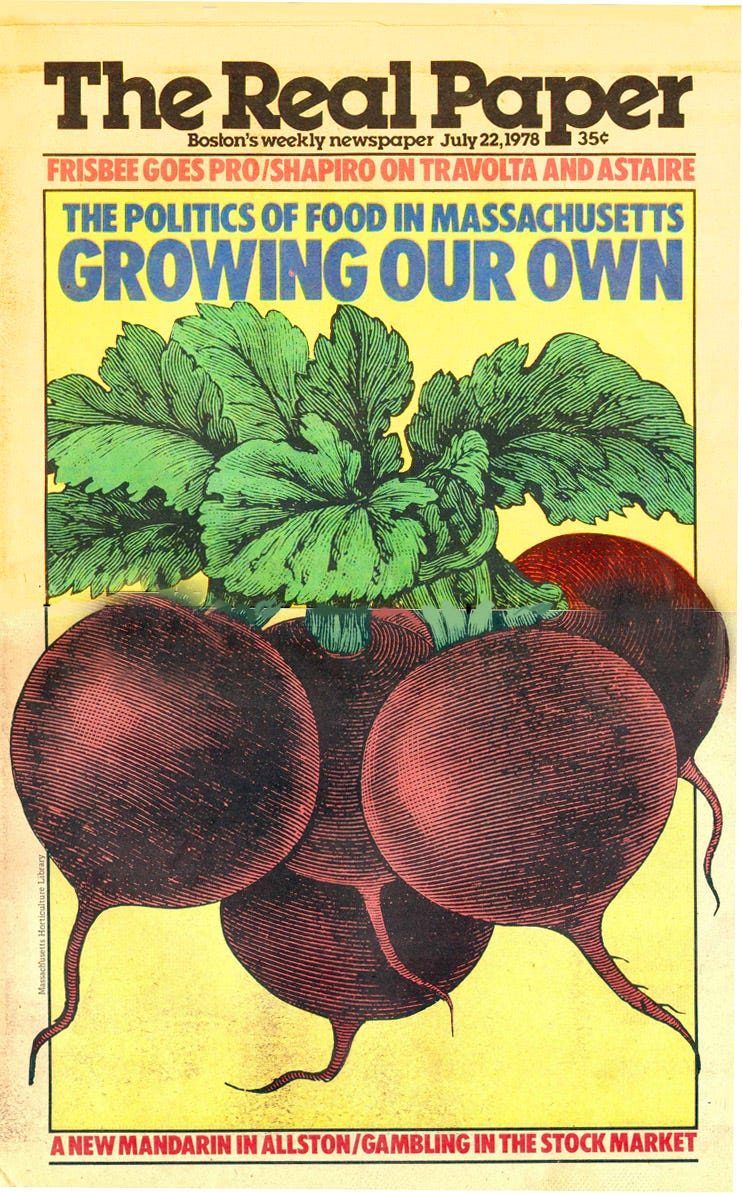

“That was protecting farmland. But it's not protecting farmers. So what do we do now to protect the farmers? And what kind of small things could we do that didn't require huge budgets? And that's when we put the emphasis on direct marketing between farmer and consumer. They said, ‘Can we reinstitute farmers markets?’”

“It's the oldest marketing system in the world,” Watson points out, “And it bypasses all the middle people. The wholesale marketing system benefits all the people in the middle, and the two sectors that we want to help the most, the farmers and consumers, are the ones that get screwed. Susan Redlich, who was the director of the Division of Agricultural Land Use hired me because we got to know one another as members of Boston Urban Gardeners. And then one day she says, ‘Would you be willing to work on this project to start farmers’ markets?’

“And I looked at her and said, ‘I think so, Susan. Tell me what a farmers’ market is.’ And she did.

“So when she explained it to me, I could see it. I really could see it. And I said, ‘Yes. I'll do it.’

“Long story short, we did. There were no urban markets and farmers’ markets in Boston at that time. And the idea was that it would be large-volume so a farmer could come in, bypass all the middle people, and sell directly but do well in a short period of time because the farmer's time was valuable time away from the farm.

“So we did it. And when we got the system set up, we started to realize there were effects that we didn't predict. And usually when that happens, you say, ‘Oh my God, we got unintended consequences and they're bad.’ But lo and behold, what we found was that most of the unintended consequences were beneficial. So two things happened there. In the world of design science, that says you've designed it right. Because even the things that you didn't anticipate…. This is where the whole becomes greater than some of the parts.”

The markets functioned as a trimtab, Watson Explains “Because we had been preaching diversification of planting forever, right? You know, ‘Get away from monocropping. You've got to diversify.’

“What most people didn't realize is that the wholesale market forces you to monocrop, right? ‘Bring me in a large truckload of this.’ And so farmers were forced to monocrop.

“Harry Currier was a farmer who came into Dorchester from Orange, Massachusetts, all the way at the western end of the state. And we used to say, ‘Harry, does it make sense for you to do that, to drive all the way here?’ He was selling cucumbers and potatoes.

“And then finally he said, ’You know, I think I've got to diversify if I'm going to do well here.’ And so not only did he diversify, but Harry Currier, who was about 60 years old, a White farmer coming to Dorchester, with all the rumors there were about how you would never make it out of Dorchester with your money alive.”

Those rumors were ubiquitous by the way. When I was a kid, for White suburbanites who drove into Boston, the rule was to fearfully lock all your car doors when you drove through those neighborhoods on your way into the city.

Watson continues, “Currier did it, and that winter he came to the community farmers’ market planning meeting. And he came and he said, ‘What would y'all like to see me grow?’

“And one of the Black consumers said, ‘Can you grow collard greens in Massachusetts?’

“And Harry said, ‘Yes, I can grow collards. But if I grow collards I've got to know that the market is going to be there, because I can't sell them at the wholesale market.’

And long story short, what happened is he started growing collards and what I realized was that this was not just a transactional relationship that we had established. We really were establishing a partnership between the farmers and consumers. The impact went well beyond even what we imagine were going to be the benefits.”

The next question I ask because Joey Manaligod, a graduate student in my lab, studies food culture and how preparing and sharing culturally meaningful food is woven through with the memory and emotional associations that make us who we are. Manaligod’s work will be the subject of a future post as well.

I ask: “So what is the importance of culturally important foods, when you have these urban farming initiatives? What is the importance that they are grown? And is that an idea that sometimes gets missed?”

Watson says, “Not only is it getting missed, sometimes it creates tension. The organizing of the farmers’ markets was back in 1976 to ‘78. We didn't have farmers’ markets back then. And then the farmer’s markets took off, right? Then they were booming around the state and around the country. And then about four years ago, I was contacted by a local nonprofit. And the director said, ‘Greg, we're having a problem with farmers’ markets.’

“And I said, ‘What is it?’

“And he said, ‘As a result of us trying to make them more accessible to people, low income and People of Color, we're now accepting WIC coupons and all the sorts of federal assistance coupons that make it easier for people to access the markets.’ But they were getting pushback from some of the local residents who were more interested in keeping the markets, for lack of a better word, high-end markets. The clientele had shifted and a lot of people from Vietnam and Latin America were coming in and populating the city. And they were influencing the market culturally in that — and this is not taking this lightly — but in many countries, the idea of a market is not our idea of this orderly calm sort of place where people come in and quietly wait in line to get their food, right? And people were kind of getting offended.

“But the director could see that we were seeing cultural shifts, and one of the things that was really being emphasized was working with farmers who are coming from other countries who wanted to not only cultivate their cultural foods, a specific sort of crops, but then also have an outlet for them. And the farmers markets were clearly the way to do that. And there was some tension in the beginning. But then we realized that there was a way to accommodate that. And as a matter of fact, people would probably appreciate being exposed to these types of crops. But it meant that the markets themselves would have to take on an additional educational role. And sometimes that meant you provide the recipes. You provide samples of things. People would taste it, and say, ‘What is this?’

“And that's another reason why a farmers’ market can be such an important vehicle to do those sorts of things because you don't do that in supermarkets, right? But here, once again, the markets evolved into this new role of breaking down those kind of barriers, but also providing opportunities for people to introduce more variety of produce from other countries.

Food Justice

I was going to ask about food justice, I really was, but Watson keeps anticipating my questions. He continues, “If I could segue real quick, though, into just expanding the notion of food justice. Food justice also involves urban agriculture because it's not just the markets and the selling and the direct marketing efforts, but then who's providing the food. In Massachusetts, I can tell you as Commissioner of Agriculture I traveled around to look for Black farmers. I mean, I'm serious, I encountered maybe a handful of cranberry farmers, but for the most part, the land is owned by, farmed by, Whites. But that's the reality in the United States. I think it's something like 80-85% of the farmland in the United States is owned by White people.:

I ask, “Even in the South?”

“Yeah,” Watson says. “Because in the South, what happened, unfortunately, was a lot of the Black farmers were tricked, swindled out of their land, right? You know, little legal glitches, whatever. Black farmers also found it extremely difficult to take advantage of federal funding opportunities that their White counterparts were easily accessing. So over time they lost their land as people realized, ‘This is a source of wealth,’ right? So in a place like Massachusetts, it's especially difficult to farm, to find land.

“The urban farming movement took a step beyond backyard and community gardening, because these are folks who want to explore the feasibility of commercial farming in the city. ‘Can we do it, make a living? And how do we do that?’

“It goes back to the old organizing days of ‘How do we get the resources to be able to do that?’ And there were lots of skeptics out there. Gaining access to the land can be difficult, and especially land that's large enough to make a difference, but it was possible. Some of these were traditional open air farms, expanded community gardens. But some of them had to employ advanced technologies, freight farms, right? They were indoors. And where you saw those begin to appear on the scene, they were predominantly owned by Whites because of the investment required to make those things work. To get the freight containers and to retrofit them and the whole bit and get the computer systems and all. But we still wanted to see what we could do to encourage more investment in traditional farming.

“Tommy Menino was mayor of Boston at the time when we were doing a lot of this work. He was great. He was nearing the end of his tenure and he called a bunch of folks in that he knew from around the city that were organizers or business people, or whatever. And clearly what we had in common was community organizing. And he looked at us and his question was, ‘So what's my legacy? What should my legacy be?’

“And I thought it was a strange question, but we looked at each other and we said, ‘Urban agriculture.’

“And then he said, ‘So what can I do? How can we cement that?’

“And we talked around a number of things. And then finally we said, ‘You know what? You need to zone the city of Boston for urban agriculture.’ Because that makes it real. Nothing is real in the city if it's not in part of the zoning ordinance.

“And the other thing we said was that it will encourage investment. ‘And it will outlive you. The zoning is there and probably more than any individual farm, more than any individual project, your legacy would be that you laid the groundwork, you created the foundation for making this’.

“And he did it. It was an incredible two-year process of public meetings once a week, every Thursday. So that’s another example of how folks come together to realize there are different trimtabs (in this case zoning). There are different ways of creating the system that will support people, low income people, People of Color, people that want to gain increase access to their ability to meet their basic food needs. Part of that is you view the political landscape at that time and say, ‘Okay, what is it that we can do given the current political scene?’ So it's an interesting combination of strategic and bottom up.”

Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative

I was excited to get to a discussion of the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative, as it was Watson’s descriptions of it that really made me think of the theme of community sensemaking arising as a phoenix from the ashes. The full story of Dudley Street can be found here on Watson’s website. But to give you some basic backstory, an excerpt from the website is below.

The Dudley Street neighborhood is one of the poorest communities in all of Massachusetts, with a population of 24,000 Cape Verdean, African-American, Latino, and White residents and with one of the highest rates of unemployment and poverty anywhere in the state…We are basically an area that was defined by devastation and poverty, an area that has suffered in a number of ways—suffering sometimes even caused by well-intentioned policies and practices. The cumulative effect of this devastation was that by 1984 the Dudley Street area had been reduced to 1300 abandoned lots filled with rubble. You could stand in the middle of the one and a half square mile area that we call the Triangle, and you could literally turn in all directions and not see a building. It was an absolute wasteland, where once there had been a thriving Irish-Catholic and Jewish community.

The reason for the rubble was that, when the community resisted “urban renewal,” which would have priced them out of the neighborhood, the slumlords who were hoping to make a quick profit burned their buildings down for the insurance. It was out of these literal ashes that the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (official DSNI website is here) was born.

To quote again from Watson’s website:

The Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI) is a nonprofit community-based planning and organizing entity rooted in the Roxbury/North Dorchester neighborhoods of Boston. DSNI's approach to neighborhood revitalization is comprehensive including economic, human, physical, and environmental growth. It was formed in 1984 when residents of the Dudley Street area came together out of fear and anger to revive their neighborhood that was devastated by arson, disinvestment, neglect and redlining practices, and protect it from outside speculators… The Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative has grown into a collaborative effort of over 3,000 residents, businesses, non-profits and religious institutions, members committed to revitalizing this culturally diverse neighborhood of 24,000 people and maintaining its character and affordability. DSNI is the only community-based nonprofit in the country which has been granted eminent domain authority over abandoned land within its boundaries.

I said to Watson, “I want to ask you about Dudley Street, particularly within the context of this idea of participatory sense-making, because there was the Weekly Anthropocene interview that you did where you were talking about it that really made me think, ‘Oh, my God, this is what he's doing.’”

“It really is what they were doing,” Watson responds. “I mean, I benefited from being actively pursued to become Executive Director when the current director left. This was after my being at the Department of Agriculture. Dudley Street Board hired a headhunter and I got a call.

“So I went in and when I really got a sense of what they were doing — I had known, from reading, that it was truly amazing — but what really did amaze me more than anything was the systems thinking that they were already using. And this notion of empowerment and self-governance. It was truly remarkable, the sophistication that was brought to bear. And their notion of participation based on who they were and where they were. I mean, they had this notion of an urban village. And their idea of a community did not coincide with any official census blocks or city. It's like, ‘No, this is Dudley, and it's here.’

“And they made a point of really solidifying that ‘We are going to define who we are as a neighborhood.’

“It was truly remarkable. And they were like a phoenix, right? Because they grew out of this incredible crime of their community being just devastated. First of all by redlining disinvestment, racism, and then eventually the torching of buildings when they objected to an urban renewal project and the speculators felt, ‘Oh my god we're going to lose our money because now we can't sell.’

“And so the speculators said, ‘Well, we'll minimize our losses by collecting insurance and literally burn the neighborhood to the ground.’

“And at that point the community realized, ‘We need to gain access to this land.’

“They said, ‘We need a vision of who we are.’ And a village emerged as the vision.

“As they would often say, ‘We don't need outside helper consultants to help us dream. But we need outside help to make it happen.’

“And that's when their lawyer said, ‘You've got to have access to the land. And there's one tool you can use.’ And they proposed the power of eminent domain.”

So – another legal trimtab – eminent domain.

Watson continues, “The political context was that Ray Flynn was the mayor of Boston. He had been in the contentious mayoral campaign against Mel King, the first African-American to run for mayor. Flynn won, but felt that he lost the community in the process. Flynn says, ‘Tell me whatever it is that you need. I'll get it for you. What do you need? Do you need rakes and plastic bags to clean up whatever?’

“They said, ‘No, we want the land. We want the power of eminent domain.’ And they got it.

“And here's an interesting caveat to that. Even in their own meetings the community argued back and forth. ‘How do we know that we can deal with that kind of power? How do we know that it's not going to be abused or just taken?’

“And that's when they said, ‘Because we're going to set up a system of governance, we're going to have a 30 member board of directors.’ It met the first Wednesday of every month. I was there for four years and there was never a question of quorum. Ever. Because they had control over their fate. The board was elected and it was representatives from Latino, African-American, Cape Verdean, and White, and then the Community Development Corporations. They encompassed all the various sectors and interests, and you're represented with three members on this board and no elected officials. Period. No politicians were allowed on the board.

“So they were doing this systems work, and I looked at them and I said, ‘My God,’ I said, ‘I wonder, would you be willing to go to a meeting at MIT if I could arrange it with Jay Forrester?’

“Jay Forrester was the father of applied systems thinking, urban dynamics, system dynamics. He was at MIT.

“And they said, ‘Well, yeah, we'd like to.’

“And I called Jay Forrester and I said, ‘You know, Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative? I wonder if we could come in and talk to you about our approach?’

“And he paused and he said ‘I'd be honored.’ And me, the nerd, of course, I had a copy of Urban Dynamics to go and have him autograph it.

“When we met we explained how we had used the power of eminent domain, and the community's vision and their collective power, to ask how they could address the problem of the inevitable linkage between gentrification and displacement. ’We want gentrification,’ they said. ‘We want to lift ourselves up. We want to improve the value of our property. But we want to discourage speculators.’

“Because these were homes that were subsidized and they were sold at low prices, but their value was greater. Prime stuff for a speculator to come in and try to buy them all up. And the community was presented with an option: The land was in a community land trust. So the homeowners owned their homes, but not the land. And that was a huge debate as well, right? Big discussion. ‘What do you mean we don't own the land?’

“And there were cultural differences. I mean, the Latinos, they said, ‘No, no, no, no. That's a source of our wealth.’ But they finally got over that when they understood how community ownership of the land can preserve their wealth.

“And then the decision was made where collectively they said, ‘We will depress or limit the profits that can be made on the resale of your home.’ This was for an extended period of time, longer than what traditional banks would consider, as a way of trying to ward off speculation. What that meant was they were limiting a source of wealth, right? So they were being asked to limit that for the good of the whole.

“Some of the banks said, ‘No, what are you crazy? Who’s going to buy a house under those conditions? ‘

“And the community kept saying, ‘People who want to live here, not people who want to speculate.’ I think finally they got one bank to take the risk.

“We mentioned that to Jay Forrester and he says, ‘See, this is amazing.’

“He says, ‘So I'm a systems thinker, and I understand that what you did was you introduced enough negative feedback into the system to thwart speculation. But, you know, here I am, a professor at MIT. I didn't know what a community land trust is. I didn't even know that that would be an option.’

“And I said, ‘That's why we have all these people. That's why we have a network. That's why we have a bunch of people who bring in different perspectives and different tools.’ And he just smiled and nodded.

Cuba

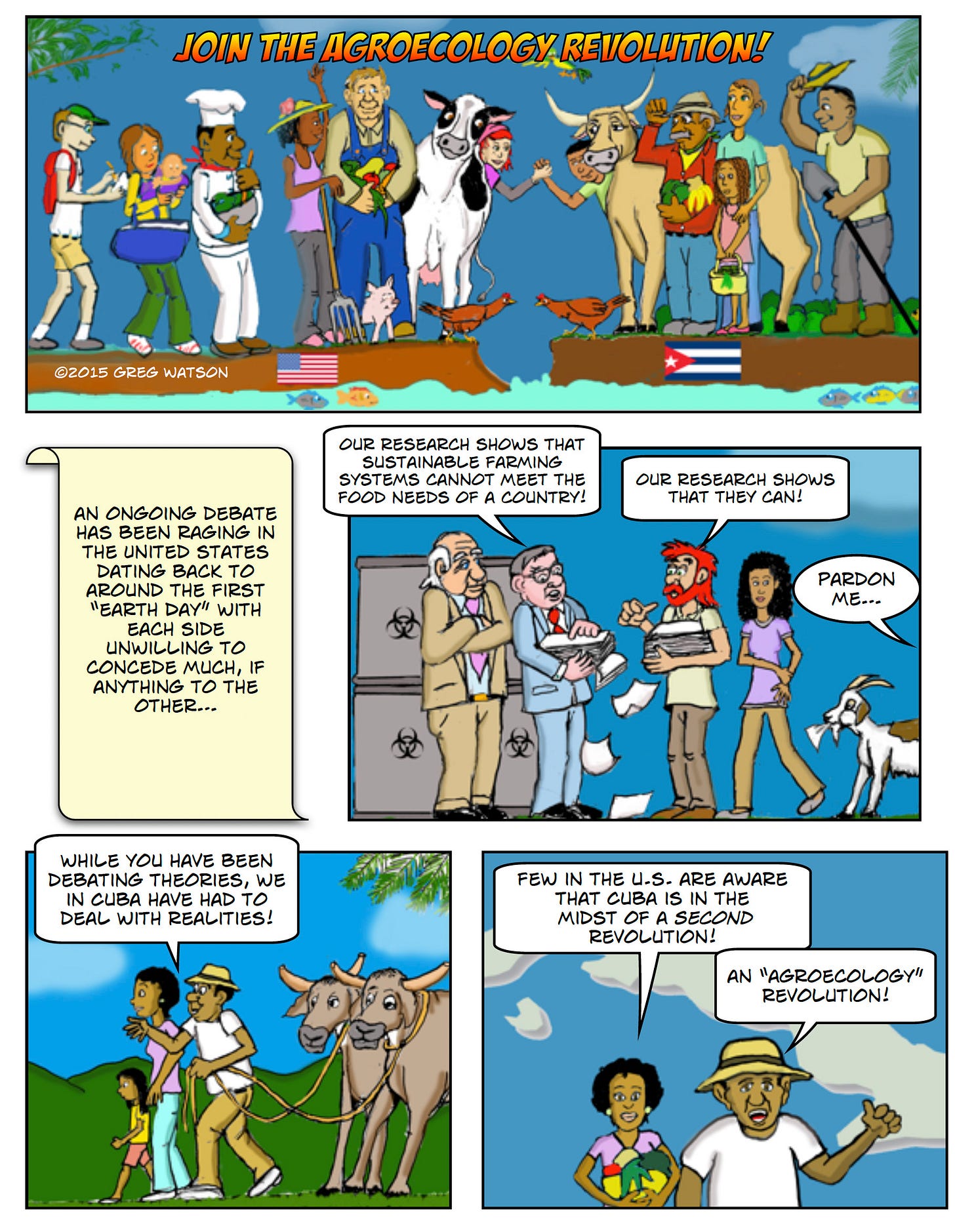

This is where I mention, “One thing I noticed when you were talking about Dudley street and what I was reading about all of the Cuban co-ops and initiatives is that both of those only arose or self-organized out of devastation, the one out of the devastation of the neighborhood that was literally razed and the other one out of the embargo which seemed to force that kind of collective creativity.”

“Yeah, that's absolutely right,” says Watson. “I was serving my second term as Commissioner of Agriculture, and I was then on the board of the Schumacher Center. And at one of the board meetings, I mentioned the fact that I was trying to initiate an urban agriculture funding program. And one of the board members just happened to ask, ‘Are there examples of successful urban agriculture anywhere?’

“Fortunately, my son, Travis, was a self-taught student of the Cuban revolution. He said, ‘Pops, yeah, Cuba, you got to tell them Cuba.’

“And then Susan Witt, the director of Schumacher said, ‘Oh, can we organize a delegation to go take a look at their sustainable food systems?’

“Because Travis had mentioned it to me, then I started reading, and it was more than agriculture — it was agroecology. The whole context was that the Soviet Union had provided them with the oil and fossil fuels that allowed them to ship across the island and to fertilize and the whole bit. And then there was a collapse (with the collapse of the Soviet Union). And as I said, they adopted and embraced agroecology, not as ideology but out of sheer survival: ‘We have to grow our own food. How do we do that?’

“And I said, ‘That's the example that I think would be important to see.’

“Susan said, ‘We’ve got the money to organize a delegation.’ And she suggested — I was going to suggest it, but fortunately she suggested it first — she said, ‘You've got to ask Travis to come with us.’

“And that was just the most amazing thing I can tell you. I mean, for both of us to do it even though his wife was pregnant with her first child.

“And it was still a dicey time there, right? Americans still couldn't use credit cards. Everything had to be cash. And what we wanted to do was see everything about it — the warts, how it was working, and what we could bring back as a result of that. And, you know, it was interesting, it was about urban agriculture, but really it was more. It was this sense of solidarity. There was this sense that ‘This is who we are, and this is really a big part of our identity.’

“And they embraced agroecology. Not uniformly. Some people were still sneaking in fossil fuel fertilizer. But what I sensed was that sort of like that same sense that I got when I was at Dudley Street, of a community and this palpable sort of pride in who we are, even though we still are poor.

“They were given the opportunity to be certainly one of the first, if not the first sectors in Cuba to form their own cooperatives and to actually make money doing it. And my goodness they were doing these amazing things. I mean, they had barbershops at the co-op, they provided some essentials. And their farmers’ markets were the outlet for most of their sales. So it was for all the reasons that you point out earlier, the similarities between Dudley Street, arising out of really disastrous circumstances and emerging to realize that one of the first things you want to do is empower people through their ability to provide basic needs — and food being obviously number one. It was incredible. And, you know, we actually tried to take steps towards forming a Cuba-US agroecology network and, for a while, we actually did exchange, and spoke back and forth and to learn from each other. So amazing experience.”

I ask, “Your report on this was written, what, ten years ago? So how has it gone since then with the opening of Cuba?“

“Well, says Watson, “Cuba still has a crumbling infrastructure. I mean, even when we were there, you would hear a boom in the middle of the night in a building would just would just collapse. And right now their grid has collapsed. And they're basically saying that there is no money and they don't know how they're going to get out of this. They really don't. “

“What about the agroecology co-ops,” I wonder. “Are they still going?”

“To the best of my knowledge, they are, but how do you survive when people now can't they don't have any… I mean, the electricity is gone. So anyway, they're in a tough time. And I don't know how anything is faring these days, which is bad.“

So, clearly, and maybe obviously, there are also limits to the amount of devastation that can support such community efforts. I hate to call it a sweet spot, but there has to be something in the ashes for a community to work with.

I continue, “So what I really wanted to ask you about is how this whole trip to Cuba and all of the projects and initiatives that you saw there then fed back into Massachusetts Urban Farming Initiative?”

Well, says, Watson, “It reinforced the notion that this is what we should be doing. It's certainly buffered the notion of organic farming. And that was already part of the thinking, but agroecology included the governance part, right? And it was interesting because in Cuba, the women are amongst the organizers and leaders, for the most part, for the agroecology movement.

“But the other thing that we learned from Cuba was the farmer to farmer exchange of education: ‘We're poor. So what we have to do is peer to peer experimentation.’ And that too was part of the idea of a cooperative — that if this farmer's trying something, and it works, he'll share that with all of us. If it fails, we will help him or her with their money, right? We'll support them to do it.

“So you've got this system that we saw that was really important. And even if not directly applicable to the urban agriculture program here, well to a certain extent it was, because not every program can get funding. So the idea would be, is there a way to create a mechanism where the successful projects, the results from the successful projects are shared with other urban farms?”

I point out, “What you're describing seems to be like that's a situation that's going to generate creativity and people willing to take risks.”

“Yeah,” Watson says. “Willing to take risks. And once again contributing to building an alternative, coexisting system. I think the biggest challenge that we have with the urban agriculture program is: Can it be economically viable? But again, if you look at the subsidies that agriculture in general gets, big agriculture could not exist without the subsidies. And of course, they're all hidden and they're dispersed, you know, pennies here, pennies there, pennies there. But if you just took away the water subsidies from California there would be no agribusiness. So it's one of those issues where I keep saying to folks, it’s interesting that the grassroots emerging efforts are always held to a higher standard than the existing system that's just been milking folks for years. But that's the way it's going to be, right? That's the way it is.

“And the other thing, there's a little bit of tension in that residents immediately said ‘Urban agriculture, cheaper food.’ And it's not necessarily the case.”

I say, “Right. I was going to ask you about that because farmers markets now are everywhere and they're wonderful, but a complaint you often hear is that people can't afford to shop at farmers markets.”

“Right. And I don't know if this is still the case, but here's one example. When we did this early on, I think it was in Dorchester, Boston Globe reporters came to the market. They said to a woman with her two children — she was buying vegetables — ’We notice that the price of the beans and peas here are slightly more expensive than they are at the Stop and Shop down the street.’

“And she says, ‘Yes.’

“‘So why are you buying them? Why are you coming here?’

“And she said, ‘Look at my kids.’

“They were eating the vegetables raw. And she says ‘If I get them at Stop and Shop and I scrape off three quarters of it into the garbage because they don't eat it, what's economical?’

“And then there was also the point about — and again, it's still part of the struggle that goes on — vegetables that they can't get at the local supermarket because they are culturally specific, right? They're looking at things that just aren't readily available or not available at all. So the variety and the cultural variety of the foods.

“But still the wealthier customers have tried to shape the market into what is more boutique-ish than back in the day when it was really funky. The early markets, right? I mean, they came, they put their baskets on the street, Dorchester, right? And funky, but direct. No overhead. And some of them would bring in baked goods and things like that, but it was more like pies. But now it's gotten into the other stuff.

“You know, that was a concern when we did develop a report to try to build a more inclusive farmers market system. How we had it and were losing it. And what we need to do to make sure that it's not lost forever. I think it's one of the things that you have to anticipate. Systems evolve as well, right? And you've always got to be concerned about who may see a good thing and decide, ‘I want to shape this more into a good thing for me.’

“And so what's got to happen is you don't want the organizers, the original folks to become too complacent because they have this thing in place. But there always can be forces that want to shape it in a different way. And so that's vigilance — you've got to be aware that that can happen and then just take the whole market out of reach for the folks that it was originally intended for. The idea of this thinking about systems is, using Fuller's terminology, comprehensive and anticipatory. You've really got to always be anticipating and the way you anticipate is you keep your eyes on both human needs and wants and trends. What's trending now? Because you can start to see the signs or the signals that the system may be headed in a different direction.”

I think about the alternative organizations of my parents’ generation, and how many didn’t survive beyond the founders’ leadership. “So some of what you're saying makes me think about passing on information to generations, because the generation that founded these organization then eventually pass on the running of them to new generations who didn't experience that initial sort of threat and challenge.”

“So yeah,” says Watson, “How do you think in a system that you want to endure, how to maintain that vigilance or a sort of gut understanding of the need for that vigilance? I mean, one of the questions is how do you do that, right? And one obvious way is that you record what goes on. And this was very interesting — when we did the Cuban trip, it was funded in part by the Ford Foundation. And when it was done, I said, ‘I'm going to write up a report.’ And they didn't want it.

“And I said, ‘I'd like to point out some things that worked and what didn't work.’

“And one of them said, ‘No, you don't point out to the Ford Foundation what didn't work.’

“Okay, so no learning. But I wrote a report anyway. I've always done that, even when people don't ask, I write a report, even if it's just for my file. And as you can probably tell, what I try to do is not to do much editorializing, but I'll include clips and others’ observations about what happened so that there's a record. That's all. And then later on, for me, the book to write is about the lessons learned.”

The Next Generation

So how do you pass on this legacy to the next generation?

Watson continues, “You know, every once in a while I work with young people who are very interesting. Conway School of Landscape Architecture grads who are doing work now in resilient agriculture. And one of the things that's happening is that they are introducing more science and technology into it. For instance, there is one group, Terra Genesis and others in a group called Earthshot where they're trying to quantify and validate the positive impacts that resilient agriculture is having. Can we actually monitor carbon sequestration of soils in a way that's acceptable that people will say, yes, this is the way to do it? Can that contribute to adding value to a particular farmer, if they can demonstrate that this is what we're doing? And some of them, like Farm Hack are working on creating farm equipment that's more geared towards the small farmer.

“And one of these young people is a guy, Tim, who was a student when I gave a talk at at the Conway School. He called me up and said, ‘Would you be willing to mentor me? Would you mind if we just do maybe a call once a week?’

“And we did it the first week, and after it was done, I said, ‘Okay, I will continue this, Tim, but we're going to call this co-mentoring.’ And it's been that way ever since.

“But the most interesting thing about him and his group is that they don't see themselves working in a nonprofit. They are entrepreneurs. And they don't do government. They said, ‘God, Greg, how much time did you burn just dealing with the bureaucracy?’

“I said, ‘A lot. There's no question,’ I said, ‘But I did find that in government I could be more strategic than maybe you can as an entrepreneur. So there’s not an either/or. And for those of us who are willing to do this work and get the policies and stuff, thank us and then go ahead and do your entrepreneur stuff.’

“And so it's been a fascinating ride. I mean, I wouldn't have done anything different. And not that everything worked, but it has been an education for me.”

In closing I want to come back to something Watson said earlier, about his early days with the Boston Urban Gardeners. You may wonder, in trying to leverage change in a complex world, ‘How do I know if I’m doing it right?’

And what I take from Watson is this: “It felt right. I don't know how else to say it. It felt right, but we were also doing the good work.”

Abundance Poem

From the participants in “Already Been Done” an Ancestral Listening Workshop from Black Feminist Film School

We have more than enough power We have more than enough energy We have more than enough light. We have more than enough wisdom We have more than enough memory. We have more than enough protection We have more than enough power to manifest what we want and repel what seeks to harm us. We have more than enough love We have MORE than enough love to go around. We have more than enough connection We have more than enough connection to love. We have more than enough mothering touch We have more than enough time, we just have to make space. We have more than enough time We have more than enough space We have more than enough joy We have more than enough stories and courage to heal our worlds. We have more than enough fire. We have more than enough peace We have more than enough activation We have more than enough meaning We have more than enough sweetness We have more than enough laughter We have more than enough beauty We have more than enough kitchen tables We have more than enough reasons to love ourselves as we are We have more than enough clarity We have more than enough gentleness We have more than enough compassion for ourselves We have more than enough intimacy We have more than enough reverberation We have more than enough music We have more than enough audacity We have more than enough breath We have more than enough examples We have more than enough bridge We have more than enough capacity We have more than enough illumination We have more than enough poetry, everywhere We have more than enough community We have more than enough pathway We have more than enough guidance We have more than enough guidance We have more We have more than enough

Thank you Rebecca for guiding through remembrances of things past and helping me gain some fresh insights into my own experiences.