A Multiplicity of Worlds

and some ways to communicate across the divides

How much better is silence; the coffee cup, the table. How much better to sit by myself like the solitary sea-bird that opens its wings on the stake. Let me sit here for ever with bare things, this coffee cup, this knife, this fork, things in themselves, myself being myself.

― Virginia Woolf, The Waves

In 2017, writer Anne Fadiman, the daughter of a passionate wine lover, published an article in the New Yorker about her quest to learn why, to her father’s tremendous disappointment, she could never learn to like wine. Her father considered her inability to appreciate wine to be a moral failing, a failure to educate her palate. But in speaking to researchers who study taste, Fadiman learned that her particular taste proclivities are a function of the number and arrangement of taste receptors on her tongue. She learned that these vary widely between people, evidence that some sensory likes and aversions arise — to a great extent — from the wiring of our sensory interfaces with the world. And that these vary more between people than the textbooks lead us to believe.

Mental health counselor and neurotechnology designer Penijean Gracefire and I have both spent years thinking about what’s basically the same question: How can two people, in the same place at the same time, perceive completely different worlds? Or as Gracefire puts it, about “Why people do and don't notice different things, and why they all seem to have these very different experiences when we're all kind of basically the same.

“How is there so much individualization of experience,” she wonders, “Given we're all in the same world? How are you going to have 10 people in a room and they have 10 really different experiences of conversation or of a party? They go home with 10 completely different impressions of how that party went. But they were all there. They heard the same stuff. They ate the same food.”

One factor, Gracefire points out, is that everyone has different sensitivities as a function of differences in the interface between their peripheral nerves and their physical environments. And they have different configurations of those peripheral nerves. “There are people who are like, ‘There's a bunch of noise, that's cool. I can just ignore it while I work on my paper.’ And other people are like, ‘I'm sorry, three houses down, somebody is apparently hammering a picture into a wall and now I can't do anything until they're done with that.’ The only way this is possible is if there is a genuinely completely different arrangement at the molecular level. “

I have a friend with a violent aversion to mushrooms, pickles, and mustard. It’s not the texture or the colour that distresses him. It’s the smell and the taste. He has other food aversions and preferences he can work around, but not these, which he calls his “Tier 1” aversions. People around him have often been convinced it’s a preference he can learn to overcome. But he can’t. For him it’s lifelong — fixed, visceral, and violent.

He describes a recent event where his partner’s roommate cooked mushrooms in their apartment. “I literally had to leave the room and put on a mask. And I almost left the building.”

The roommate was cooking reconstituted mushrooms in a cooker with sticky rice. He had been cooking them for a while, and when he opened the pot my friend smelled it from 15 feet away. “I could initially smell something that was distasteful. I just didn't like it. But a few minutes later, I almost had a gag reflex and I felt terrible. I felt a tightening in the throat and repulsion beyond all belief. You know when your body just wants to eject something? It felt like that. It was like, ‘I want no part of this at all.’

“And that lasted all day. I had to wear the mask for a few hours. In a different room, closed door, fan on, window open, trying to blow all the smell out. And it was terrible that entire night. The next day, within maybe five feet of the pot, I had the same reaction. I could still smell it 24 hours later. So I opened the door and it was 35 degrees outside. Fahrenheit.”

My mother in law has the same response to eggs in any form. You can’t cook them or eat them in any space she’s in. My husband has a violent aversion to fish and seafood – though at least he can be at the same table where people are eating them. His father had, and his sister and half-brother have, the same fish and seafood aversion.

You have to be open continually to the possibility that the people that you're engaging with are just experiencing things in a radically different way from you. And that's hard. It's hard because there's always this sense of a reality that's absolutely fully distinct from us. And there's always the sense that that reality has to be the thing that we share.

One of the central themes in theories of participatory sensemaking is communicating across difference. And there is a lot of difference. From the level of the senses on up. More, even, than we tend to think there is.

With regard to taste, there is evidence that the density of fungiform papillae on the front of the tongue, mushroom shaped structures that contain taste buds, can vary widely and this variation influences taste as well as the touch sensitivity of the tongue. The latter can make some people very sensitive to texture such as sliminess or crunch. Beyond the tongue, there are large individual differences in touch sensitivity and acuity – the ability to discriminate different surfaces through touch — that are due in part to differences in skin mechanics, skin stiffness, and the density of and distribution of multiple types of touch receptor, including those responsive to pain and soft stroking touch.

Even research on the well-mapped visual system, which typically focuses on what is common between individuals, has begun to paint a picture of variability at the level of very basic vision. For example, recent work from the lab of influential vision scientist Marisa Carrasco has linked individual differences in peoples’ sensitivity to contrast to wide variation in the size and organization of primary visual cortices, where signals from the retina first enter the cortex.

And then there’s synaesthesia, where a reasonable proportion of people fuse sensory modalities such that words or numbers have colours, or sequences of months or numbers are perceived as spatial configurations. A friend of mine – I hope to post an interview with her in the future — has a rare form of object-personality synaesthesia. To her, individual objects such as each of the elevators in a hallway, her laptop, or her shoes have distinct personalities with whom she has a range of positive to negative relationships. She isn’t making this up. When she was a teenager her abilities were rigorously probed by cognitive psychologist Daniel Smilek (he published a paper on her as a case study titled “When ‘3’ is a Jerk and ‘E’ is King: Personifying Inanimate Objects in Synaesthesia”). They are consistent and very real. “TE” lives in a vividly animate world.

My research has focused more on how we notice what’s relevant to us than on the wiring of the sensory systems themselves. I’ve spent a lot of time researching ways that personal emotional experience tunes our attentional habits so that we see or feel what’s relevant to us in a given situation. I’ve found that, building on our genetic predispositions, life tunes us to the world in particular ways. Attention is an active (if often implicit) lens for selecting some aspects of the world and rejecting others to become aware of. The take-home from that work is that we preferentially attend to and perceive and remember what we have learned is affectively meaningful — that is, what is relevant to our wellbeing in a given situation. These include words or images associated with combat experience for soldiers deployed in Afghanistan, or with the events around a near plane-crash for passengers who were saved at the last minute, or with climate change for those who are concerned about it. They also include happy faces if you’re a child or angry faces if you’re an undergraduate, or a small circular grid that you just learned minutes ago predicts a shock or some points you can cash in for a reward.

Philosopher Bryce Huebner has also spent a lot of time thinking about how differences in experience can tune our senses. He elaborates, “I think one of the deep mistakes in cognitive science is our attempt to pull the perceptual bits apart from the affective bits and the attentional bits and the intentional bits. When you look at all of that stuff operating together within the perceptual systems, one of the things that comes quickly into view is that part of what's driving the differences in how people encounter sensory stimuli is the ways that different bits of the information are being boosted, suppressed, clipped, transformed, whatever else.”

Huebner continues, “In a book that I wrote with Jay Schulkin (Biological Cognition) we've got a chapter on perception. And one of the things that we tried to center was the fact that a perceptual system should be attuned to the challenges and the opportunities that are available to a particular organism. If you start thinking about the differences in embodiment between people, or the differences in the ways that different animals are embodied, are going to shape the kinds of challenges and opportunities that come into view, you should expect forms of perceptual calibration that are partially driven by shifts in sensitivity, shifts in attention, shifts in what you intentionally direct towards. These are going to start to drive us into places where — even if there is something relatively stable in the architecture of an animal— perception is going to be tied to the kinds of things that matter for the kind of life that you have.”

Beyond the ways in which they filter immediate sensory experiences, people can also differ in their capacity to re-evoke or imagine imagery in specific sensory systems. Huebner himself is someone who has aphantasia, which means he generates no visual mental imagery whatsoever. For much of his life, he assumed this was the norm. “One of the things that was surprising to me was learning at some point, maybe a decade ago, that people really did have mental imagery. I learned about it because a friend sent me a blog post of somebody describing what the experience of aphantasia was. And as I'm reading it, I'm like, ‘Wait a second! All of this stuff that he's talking about as his experience, that's exactly what I've experienced!’

“Additionally, all of the stuff that he was like, ‘I have no idea what they are talking about’ — I have no idea what that stuff is either. People imagining future situations, people reflecting on previous events and projecting themselves into that space. People thinking about different kinds of fantasies and whatnot. None of that stuff shows up in the structure of my experience.”

Huebner explains that one exercise that is often used to test the capacity for mental imagery is by asking people whether there is a window in the kitchen where they grew up. “If I try and work through that,” he says, “ I've got pretty rich proprioceptive and bodily imagery. And what I do is I imagine the way that it feels to walk in the front door, to walk up the stairs, to turn slightly to the left and to orient myself in front of the kitchen sink. Then what I have to do is to imagine reaching out to feel whether there's a window there. I can't in that case, pull up a clear sensation of touching the window, probably because I never did it. But I can have a rich experience of the embodied activity of walking up the stairs and turning through different spaces.” In all of this, there is absolutely no visual imagery. He sees nothing in his mind’s eye, only whatever is actually in front of his eyes as he goes through the imaginative exercise, or the backs of his eyelids if they’re shut.

“The story that always floors people,” he continues, is when he tells them that “My mom was very opposed to having her picture taken. So I've got very few pictures of her. But at this point, she died 20 years ago, and I've got basically no visual sense of what my mom looked like. There are bits and pieces of things that I can sort of get a feel for, but most of it is just absolutely not there.”

It seems a particularly cruel combination of circumstances, his mother’s aversion to being photographed along with his aphantasia.

So — we have differences in the architectural structures of our sensory systems, and differences in our capacity to generate mental images linked to specific perceptual systems, and then these systems themselves are constantly tuned to grapple with what is relevant to us given our life experience. These are strata of ways in which our more basic and higher order sensory architectures predispose us to engage with particular affordances of the world, and then, on top of that, our histories tune us even more.

Now here I want to add a caveat, and refer back to my previous interview with Ezequiel Di Paolo, who stresses the importance of maintaining the capacity to grapple with paradox. For all that I’m emphasizing difference in this post, we of course share common experiences, common bodily and sensory architecture, and common patterns of brain activation. At a coarse scale, our brains are all organized into the consistent cortical and subcortical structures we learn to recognize in the first pages of our neuroanatomy textbooks. And there is evidence that the ways in which large scale functional brain networks respond to common experiences, such as watching the same movie, can become more similar to those of other people over childhood and adolescence. So the commonalities of both architecture and experience certainly create shared ground. But this post is about the importance of grappling with differences that can be overlooked in the light of these commonalities.

Huebner is also interested in how, beyond the factors at work in tuning our sensory systems, higher order processes related to culture further influence and are influenced by both architecture and experience: “One of the things that I've been thinking about a lot is a movement within anthropology looking at people's experiences of divine presence, people's experiences of jinn, people's experiences of ancestor spirits. Within the anthropological context, people really want to figure out how to take that stuff seriously. And I think that one of the things you really need to do to take that stuff seriously is get to the point where you can actually make sense of what it is for people to perceive these kinds of presences. And different people do it in different ways: Sometimes it's a tactile sense, sometimes it has something to do with the way that your body feels, sometimes it's seeing things out of the corner of your eyes. Sometimes it's the way that you're making sense of the information that's available in your sensory milieu. And part of what that calls into awareness is that those forms of learning and those forms of history and those forms of attunement are often deeply culturally situated. But once they're there, they present the world as having a really rich kind of character that, if you've got that, it starts to open up new capacities for coping.”

“One of the things that I love is psychiatric field work that (psychological anthropologist) Mohammed Abouelleil Rashed did in an oasis in Egypt, interacting with people who get harassed by jinn. One of the things that he highlights is that, if you're somebody who interacts with jinn, you can reason with them. Not always, but you may be able to give them the sorts of things that matter to jinn, and that can help to dislodge some of the negative effects of those sorts of possession experiences.”

In contrast, Huebner points out, “No matter how hard you try, you're not going to negotiate with your neurobiology. I’m not the kind of person, given my history, who can encounter jinn in that way. But that means that I lack capacities for navigating those challenges if I end up in a similar sort of perceptual space because of whatever kind of psychiatric difficulty I'm experiencing. If I start to see the beings who are harassing me, I probably can't get to the point where I can have conversations with them. And I probably can't use the tools that other people working in that space could use to navigate that. And I think this is one of the reasons we have to really think deeply about what's going on with the perceptual space. The way it's coupled to our social space and the ways that that starts to change the challenges and opportunities that are available for any of us.”

However, technology is now providing tools to create euro-anchored perceptually grounded stand-ins for jinn. Huebner points to an article in the Guardian by Jenny Kleeman. The article reports initiatives to help people living with psychosis to navigate these kinds of experiences conversationally with avatar therapy, using technology to create embodiments of their persecutors so they can talk back to the voices in their heads.

At a more basic level, Gracefire has focused on individual differences close to the perceptual space Huebner refers to, in the organization of the sensory systems themselves. “We're all familiar with the concept of color blindness. We all know that not everybody has the same rods and cones and sees colors the same way. We know that there's differences in these ways that we perceive the world. We know that there are some people who are tone deaf and that there are some people who can hear everything.”

As the wine-appreciation story illustrates, she continues, “there is this idea that there is a right and a wrong way to like stuff or to not like stuff. That there is a right and a wrong way to perceive art or to appreciate wine. Or to have a taste in fashion or to assemble different colors together into an outfit. That there is a right and a wrong way to paint with different colors that go or don't go. I'm sorry, if you don't see those colors is it wrong for you to put the colors together you see? And if someone who sees a lot more shades doesn't like it, are they right or are you right?”

…Maybe I can create neurotechnology that allows for more efficient processing speed so that we can potentially hold more data bits simultaneously in our minds. If I can reduce that rigidity, if I can just make it more efficient to take information in and to consider it and to hold more data bits simultaneously — then maybe I can help people to experience the possibility that other people are not the same as them in a way that could be interesting as opposed to overwhelming.

For Gracefire, these value-loaded differences in perception are foundation stones for problems with relationship, and relationship is what she’s really interested in. Here her questions start to sound very similar to Huebner’s.

“The thing that has always interested me from the beginning is: Why do I notice stuff that other people don't notice? And why do they notice stuff that I don't notice? And what are these sensory inputs from which we construct a reality that we use to engage in relationship or we use to relate to people? I'm defining compatibility such that not only can you and I agree on some common tent poles of reality, but we also are drawn towards and enjoy interacting with certain sensory components of our environment in similar ways so we derive satisfaction or enjoyment or fulfillment.”

These questions have preoccupied Gracefire since she was a kid. “The experience that I was having of my environment did not seem to be the experience other people were having of their environment. I did not seem to be relating to my environment in the same way as other people were in ways that made me compatible. So either I did not desire to be proximate to them or they did not desire to be proximate to me. And I think a lot of people can actually relate to the idea of feeling different or weird.

“So if we're all feeling a little bit different and weird, maybe everyone struggles to fit in and we're all trying to figure out what the rules are. If most people feel that it’s work to relate to other humans, what are the mechanisms of why? Because we're all interacting with the environment in somewhat similar capacities.

“And so I kept questioning why. ‘Why do I feel different? Why does this not work? How can I potentially be more compatible? How can I find people who I relate to? Why is it so much work all the time to try to relate to other people? This is a lot of energy. Surely there is a more efficient way for me to do this. So I'm not just struggling constantly to understand other people's points of view.‘

“This is just the basics of theory of mind,” where you understand that “‘I'm me, you’re you, you have a different experience than I have. You have an experience of me that I don't have. Your experiencing me affects how you interact with me. So your responses to me could impact how I then act towards you.’

“And if these mutually modulating feedback loops are active, if people on both sides are paying attention and trying to figure out how to be more compatible, then you've got some degree of communication and relationship that's sustainable. But I think that only happens when people are interested in the other person. And they think of them as other entities with different experiences and different perceptions. And I think there is a critical mass of humanity that is struggling with that basic concept.

“ I don't know why this is so difficult,” she says, “but I am leaning towards the idea it is maybe a bandwidth problem.”

Gracefire continues, “I want to call it a big problem because of the natural limitations of how many things we can think about at a time. We can't actually think about all of them. There are too many. So we reduce and simplify and bin people into categories and then decide which categories are worth inclusion and which categories are not. Black and white thinking or binary thinking or, you know, thinking of less than three data points simultaneously is really just small bandwidth thinking. It's just, ‘I just can't hold too many options,’ right? There's good and bad. There's light and dark. There's the in-group and then there's the out-group.” (Note - for a philosophical view of the importance of thinking in multitudes rather than binaries, see this piece in Andrea Hiott’s Waymaking substack.)

“Because you could have five friends who are the same and one friend who's different and that might be fine, right? But now you've got two people in your friend group that are really different from you. Now you've got three people in your friend group who are really different. None of us like the same food. None of us look the same. None of us have the same cultural backgrounds. Now I’ve got to remember ‘Okay, well, you want to be called by these pronouns and you only eat this kind of food, and you have these kinds of allergies, and you feel like this about this kind of music.’ At some point, if I'm going to actually care about, pay attention to, consider and be compatible with them, how many degrees of difference can a typical human being hold simultaneously? I think that there is complexity fatigue.

“So if that's true, then I think really the core question becomes: Are people capable of saying ‘I have a construct that I use to interact with the world and I cannot assume anyone else is operating from an identical construct. So anytime I interact with anybody, I need a praxis for establishing some degrees of commonality, which I can use as reference points to achieve communication and mutual visibility?’

”Just as intimacy is seeing and being seen, right? How do I understand their perception of me so that the inputs I put into the mutual modulating loops are actually communicating the things I want to communicate? So if people can't comprehend this is potentially how it is, how are they even going to develop a stance for interacting with other people?

“I don't actually have a good solve. The only thing that I've arrived at to date is the idea that maybe I can create neurotechnology that allows for more efficient processing speed so that we can potentially hold more data bits simultaneously in our minds. If I can reduce that rigidity, if I can just make it more efficient to take information in and to consider it and to hold more data bits simultaneously — then maybe I can help people to experience the possibility that other people are not the same as them in a way that could be interesting as opposed to overwhelming.”

For his part, Huebner has been grappling with the same question. Coming at it from the level of culture, Huebner says “Communicating across different modes of experience — how do you even start to think about it in a plausible way? How do I start to think about somebody who has really experienced being possessed by jinn and have a dialogue with them given that there's so many spaces and dimensions of my world that are not the spaces and dimensions of theirs and vice versa? The key question becomes, how do we communicate across differences? Even with people that we spend lots and lots of time with?

“This is where the view that I think is plausible comes into view. You have to be open continually to the possibility that the people that you're engaging with are just experiencing things in a radically different way from you. And that's hard. It's hard because there's always this sense of a reality that's absolutely fully distinct from us. And there's always the sense that that reality has to be the thing that we share. But all any of us have is a perspective that is disclosing whatever part of reality it discloses. If that's right, and if we can accept it, we can have a conversation where I can try and figure out which part of the world you're looking at, and where you can try to figure out which part I'm looking at. Those conversations can be hard. But in the grand scheme of things, they're pretty trivial. It takes work, but if we can really make sense of us sharing a world in a rich sense, even though things seem so different, then we can have open and exploratory conversations that reveal the world in richer complexity.”

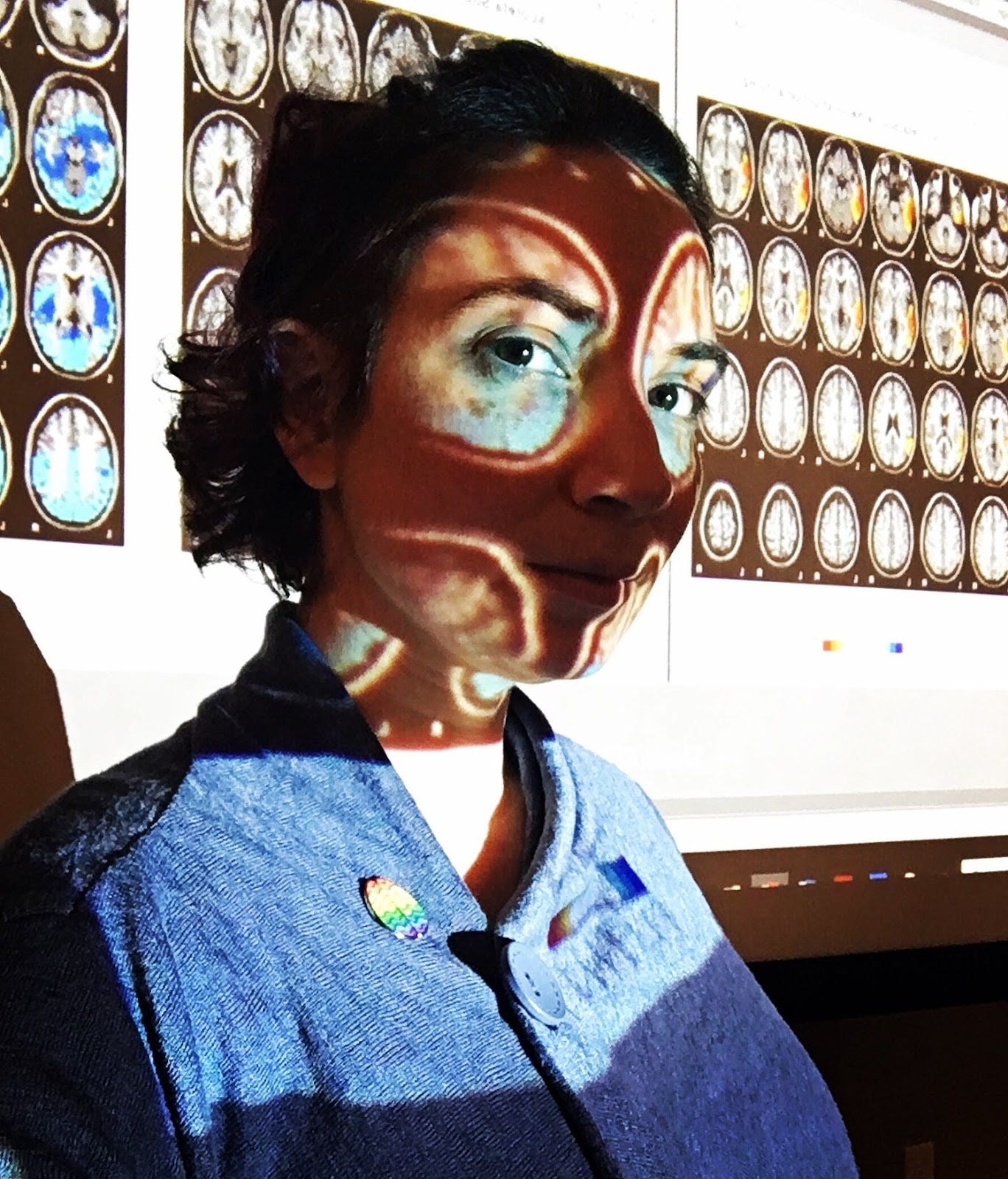

Neuroscientist Naila Kuhlmann is trying to seed exactly that kind of conversation through art — art that incorporates the body and technology, circus and science, to communicate what it’s like to walk in another’s very different pair of shoes.

It took a while for Kuhlmann to come to the strategy of bringing art and science together to facilitate communication across differences, in particular differences related to neurodegeneration. For her PhD research, she studied a protein called LRRK2 in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. She was, she says, looking under a microscope for six years, but her understanding of Parkinson's remained fully academic. She realized she wasn’t actually interacting with anybody living with Parkinson’s, and had very little understanding what they might be living day to day. At the same time she was dancing every night. “I almost wanted to leave academia to pursue dance and circus,” she says, “and so a lot of my thinking was shaped through dance and through movement and through how the body is our way of relating to the world and others.”

Ultimately Kuhlmann scaffolded a very embodied form of research/communication. Her postdoctoral research in Montreal increasingly uses art and science to communicate lived experience. In 2018 she started a group called Piece of Mind Collective as a side project, bringing together neuroscientists and dancers, circus artists, musicians.

She recalls, “We had our first meeting in a park over a picnic, and at that point it was just about neuroscience and performing arts collaboration. We started working on a piece that was to represent genetic mutations in Parkinson's through dance and music, from the genetics to the protein level, and what that changes in the brain. And then someone very astutely said, ‘We shouldn't be doing a piece about Parkinson's without involving people with Parkinson's.’

“And that's where the light bulb went on.”

This collaboration, which unfolded during COVID, resulted in two beautiful and moving dance-theatre-circus performances —which were filmed and can be viewed here. Watch them! You’ll be glad you did.

Her current project builds on Piece of Mind, with the goal of using technology to allow audience members to go beyond seeing Parkinson’s disease depicted onstage and feel some of what the experience of living with Parkinson’s — as well as the experience of being a circus performer is like — in their own bodies.

But communicating across difference is hard. This is where Kuhlmann and her collaborators have struggled with the degree to which it is possible, or even desirable, to evoke empathy or simply convey information about very different experiences. For example, you can put an armband on someone to give them the experience of an involuntary tremor. But what, exactly, of the experience of Parkinson’s does that communicate? “I think as we've progressed in this project, it's brought up a lot of questions such as how and what creates empathy,” she explains. “Do you really need to put something into your own body to understand them, or to accompany someone better? And when is putting on an aspect of someone's experience reductive and maybe counterproductive because it could lead to a real simplification of what someone is experiencing over time in a holistic, complex way? Now we may be reducing it to putting on a tremor armband, which doesn't begin to capture the whole of it. So in breaking it apart are we actually doing a disservice to better understanding the experience?”

For example, in Kuhlmann’s project there is one collaborator living with Parkinson’s who said something like, ‘You can feel what the tremor of my hand is like, but that's a small part of my day and it doesn’t communicate the whole emotional journey of coming to acceptance with the experience over time.’ In his experience the tremor is a part of him. And the band also doesn’t capture the social aspect which is often the more disabling aspect. He says that he’s fine with the tremor until someone else sees it and projects something onto him. That's when he wants to hide it.

On the other hand, Kuhlmann also wants to communicate the embodied experience of what it is like to be a circus performer. She explains, “One thing that came out in Piece of Mind is that despite being very different experiences in the body, (Parkinson’s and circus) both bring a greater awareness to movement throughout the day, and to how we learn or relearn movement. There is also the performance aspect, whether as in circus you where choose to be in the spotlight, or (as in Parkinson’s) if you have a condition that affects your movement and your speech and you are thrust into the social spotlight in ways that you don't choose. There is so much rich conversation between these two standpoints of embodied difference. A circus artist has a whole different relationship to objects and to gravity and to motor control than I do, and in Piece of Mind we see circus artists suspended from their hair or on tight ropes or upside down. I was curious about how technology can be this doorway into those two experiences and those two different standpoints on what it is to be an embodied being and a human in the world.”

Through collaborative art, Kuhlmann is trying to enact and inspire communication about experience across divergent patterns of sensorimotor wiring.

In contrast, Gracefire’s approach is to target brains directly, perturbing individual brain systems so that they are better able to enter into such interactions.

“What ended up driving me into neurotechnology was trying to find a vehicle for communication and connection. So all the conversations we've had up until now are essentially about me trying to understand and identify the barriers. When people can't do that, how do I fix it? Because I can tell them words. I can show them pictures. We can discuss skills and ideas and dating strategies. But in the end If your brain doesn't comprehend the same stuff my brain does, it's got to happen at the brain level, right?

At the level of neuronal firing patterns, Gracefire explains, what she’s describing as bandwidth problems or difficulties with social interaction are often linked to rigidity in the firing patterns of local populations of neurons. Rigidity at the local level in turn influences the capacity to engage larger scale networks in a way that serves flexible and efficient cognition.

Guided by an intimate familiarity with the wiring of key neural circuits, her goal is to identify the relevant nodes of networks whose activity is limiting capacity, and then perturb them so that the pattern of activity becomes more flexible. This is not a straightforward task. As she puts it, “How do I take a brain that's doing hundreds of thousands of things simultaneously and identify the areas and the temporal frequencies that I want to interact with? So that I can say, ’Hey, listen if you could (integrate) these areas together on these same frequencies at the same time, I bet it would be easier for you to give a presentation at work without having a complete meltdown.’”

Gracefire concludes, “I think my biggest regret about the way our world works is the fact that, because of our bandwidth difficulties — because of the bandwidth limitations of people who make decisions for everyone else – instead of us supporting and expanding and appreciating our degrees of difference and complexity, we reduce and we categorize and we simplify and we marginalize and exclude. Because it's too hard and it's too complicated to pay attention to everyone, to meet everyone's needs, to be accommodating. It's too hard to include everyone.

“I don't know if we're ever going to have a shift away from exploitation and excluding the least exploitable to expansion and accommodation and integration. I don't know if that's ever going to happen, because I think we're always going to run into the bandwidth limitations that we have cognitively. But I love the idea that I could maybe help build a thing that increases that bandwidth.

“If we can increase people's bandwidth in general, then that's where there's really potential to move inclusivity to the next level. Which would be pretty cool. I think if we rely on external circumstances that it will not happen anytime soon. And I don't know that I can make it happen at the individual level.

“But I do certainly borrow from many of my activists and academic friends who essentially say ‘The work sucks and you'll die before it ever comes to fruition, but it's still worth doing.’”

"How can two people, in the same place at the same time, perceive completely different worlds?"

What a post.

So many threads tying together as I read it, so many interesting projects and people (and photos). I'll have to read it again and still need to watch the video but wanted to respond right off because: It is inspiring to see these questions articulated and addressed as they are in this post and by those who are part of it.

What Bryce Heubner says about the embodied wholeness of how we might understand your question above really resonates. Also, Gracefire and this way of discussing neurotechnology is refreshing in these times, a healthy holding of the paradox. Kuhlmann's work and the Piece of Mind collective is an inspiring template for how we might reimagine academia in everyday life...It makes me think of how our creations (our books, movies, etc) are ways we try and 'share our embodiment' with others, ways we start to understand this same starting question above...

Our technologies at their best could do this too? In grad school I was fascinated by this project The Machine to be Another (https://beanotherlab.org/home/work/tmtba/) which tries to do this virtually, and I still think about how technologies might be ways we can better experience our multiplicities.

wonder-full